|

|

||||

Written during Ronald Reagan’s first presidential bid, Mamet's

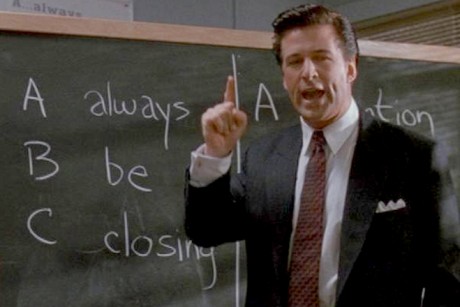

greedy men almost seem quaint in our impenitent era BY MARK GUARINO SUNDAY, OCT 21, 2012 06:00 PM CDT Maybe it’s the carpet-bombing cursing or maybe it’s the blunt poetry of the Chicago streets, but David Mamet’s 1984 Pulitzer winner “Glengarry Glen Ross” is always reliable for striking the doctrinaire dramaturges and other gatekeepers of the Broadway stage as a noble beast of a play for how it swings the double-edged sword between a game of grotesque verbal handball and a finely hewn critique of human greed. You know the drill: A storefront real-estate office in Chicago gets jacked of it prime leads, setting in motion a buzzard’s den of penny-ante salesmen who argue, whine and eventually knife each other in the back to survive, just like they do in the cubicle farms that grow the worst in human relations. This harsh allegory of modern-day capitalism is not for the frail. New York Magazine critic John Simon famously freaked out on the play, calling it “reprehensible, immoral” because Mamet “enjoys his characters too much, that he revels in their brazen, agile crookedness.” He may be right, but did it matter? The mall crowd that discovered “Glengarry Glen Ross” a decade after its star-studded film version weren’t offended. In fact, Mamet catered to their palate by shoehorning a brand-new monologue into the script that, performed by a young and skinny Alec Baldwin, upped the ugliness, multiplied the F-bombs and introduced to the play an actual set of brass balls. The thirtieth-anniversary production of “Glengarry Glen Ross,” which opened in previews on Broadway on Friday, October 19 at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, is the bridge between the hapless Willy Loman of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” and the heartless man pigs of writers Neil LaBute, Martin McDonagh and other contemporary Mamet men. In Loman, Miller saw capitalism setting a rattrap for Middle America’s dreams, but Mamet’s salesmen are not just stuck behind bars, they’re placing the bait and pulling the string, too. Blame it on generational distrust — “Glengarry” was written in the wake of Watergate, Vietnam and other landmark atrocities of the Baby Boomer era, and in the recent glow of the “Morning in America” bluster that marked Ronald Reagan’s first bid for president. Willy Loman retreats into his fantasies to escape the reality he isn’t going to have a place setting at Eisenhower’s Formica kitchenette, but the Chicago salesmen of Mamet’s play have it worse: They’re at one another’s throats like wild animals trying to get on the office scoreboard in order to win the prize Cadillac Eldorado. The fatigue of clawing through life this way is not lost on Richard Roma, the office’s top-dog closer who delivers the play’s heartbreaking coda: “It’s not a world of men … it’s a world of clock watchers, bureaucrats, officeholders … what it is, it’s a fucked-up world … there’s no adventure to it.” The current revival of “Glengarry” arrives at a time ripe for thrashing aggressively greedy males. The Occupy movement of 2011 forced a national debate on economic inequality, revealing data that would make Roma reach for a Rolaid. Example: An October 2011 report by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office found that the average inflation-adjusted, after-tax income for the top 1 percent of the population grew 275 percent between 1979 and 2007; in 2007 alone, the top 1 percent earned 23.5 percent of the nation’s total income, the second highest gain since 1928. By contrast, for wage earners at the bottom of the economic ladder, the average after-tax household income rose 18 percent. The early recovery isn’t closing the income gap either. A 2012 study by French economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty shows that in 2010, considered the first full year of recovery, 93 percent of the income growth went to the top 1 percent of the U.S. population. Their average income jumped about 12 percent, while the average income for the bottom 90 percent remained at its lowest level since 1983. Behind those numbers lies the brutal truth of “Glengarry”: that when the bottom line among individuals is purely to get that buck, no one leaves the room not debased in some awful way. The play rotates through a series of negotiations by these five men, and none of them emerge ahead of the other. The only virtue they are left with is swagger. “Whoever told you you could work with men?” Roma fires at John Williamson, the office manager, after he unknowingly scares off a client Roma is trying to prevent from canceling his contract. The line, like many in the play, is intended to be a dagger thrown to wound the opposition. Today, Roma’s words would hang in the wind in the face of the opposition’s legal team vested to block each syllable. The CEOs, financial managers, venture capitalists, corporate attorneys, real-estate honchos, bank presidents and general modern-day robber barons who perch atop the nation’s economic systems are generally invisible, their personal identities hidden behind walls of legal documents, lawyers, lobbyists, public relations and personal security experts that sanitize every action they make, legal or no. The reckless trading that ignited the credit crisis and subsequent collapse of Wall Street investment houses and that sent the economy spiraling did not have consequences for anyone except the people on Main Street, but that mattered little. The finger pointing done on city streets, in Op-Ed pages and on the campaign trail rallied the populist base but did little to shame, or even diminish, the actions or intent of the reigning elites. That’s because consequences, like those portrayed in “Glengarry,” no longer play a role in this new era of mountaintop capitalism, where so few control the fate of so many while being so vastly removed from the actual sale. When Shelly “The Machine” Levene, the hapless old-timer of “Glengarry,” ridicules Williamson for having no skill or talent in old-school salesmanship, he sounds quaint by today’s standards: “That’s cold calling. Walk up to the door. I don’t even know their name. I’m selling something they don’t even want. You talk about soft sell … before we had a name for it … before we called it anything, we did it.” With the advent of online commerce and curious investment products like hedge funds and derivatives, the hard-scrabble code of conducting business has long been replaced by proxy armies and online contracts that hold no one accountable but you once you click “Agree.” Globalization groomed companies to streamline how they interact with the consumer, which is as little as possible. Phone banks in third-world countries, online portals that go nowhere, byzantine term agreements — they’re all designed to make one side win the gun fight, but without anyone needing to load a bullet. How much we’re forced to play chumps in almost every interaction we make outside our personal circle should, in theory, make us stick our head out the window and tell the world we’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore. But that’s the movies. The ultimate triumph of “Glengarry Glen Ross” is that it now reveals less about the scheming salesmen and more about Jim Lingk, the henpecked husband who shows up near the end to nullify his contract for the Florida swampland he purchased the night before in a liquor-induced haze. As Roma and Levine swarm in circles to persuade him otherwise, we can recognize in Lingk’s stammering a similar embarrassment at being dropped in the shark tank. After all, who wouldn’t feel feeble accepting increasing transaction fees for no reason, discovering you’ve been double billed but can do little about it, being forced to give up your personal information every time you make a purchase online or find out your health insurance doesn’t cover your pre-existing condition? At the end of the play, Lingk responds with the only logic the situation is due: “Forgive me,” he says. Then he runs out the door. Mark Guarino is on staff at the Christian Science Monitor. He lives in Chicago. MORE MARK GUARINO. |

||||