|

The Kinship Between Talk Radio and Rap |

||||

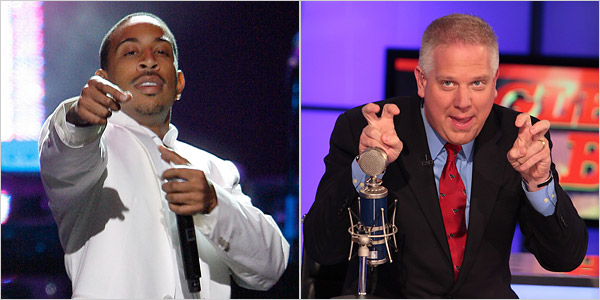

September 20, 2009 By DAVID SEGAL If you’re driving alone through the plains of Nebraska and need a little company, you can’t do better than the nationally syndicated maestros of political talk radio. Hour after hour, rant after rant, it is a feast of words and feverish emotion, interrupted only by regular commercials and the occasional call from the awe-struck fan. I’d heard these voices before, but only in sound bites. When you don’t own a car and don’t tune in at home, you probably don’t run into Michael Savage, Rush Limbaugh or Mark Levin. On the highways of the Cornhusker State, they ran into me, every time I hit the scan button. After a while, it felt like a series of visits from very colorful and highly agitated relatives. Or it would if I had a lot of relatives certain that America is slouching toward a socialist abyss. The apparent influence of these conservative talk professionals has caused more hand-wringing than usual in recent weeks, in the wake of our summer of angry town hall meetings and the “You lie!” outburst of Representative Joe Wilson of South Carolina. And when you hear Barack Obama likened to Pol Pot — as Mr. Savage did in a recent show— you can understand the concern. But to my uninitiated ears, there was something reassuringly familiar about political talk radio, and not because I know a lot about firebrands. It’s because I listen to a lot of rap. Gangsta rap, in particular. I’ll admit that the parallels between Jay-Z and Rush Limbaugh do not seem obvious, and to grasp them you need to look beyond the violence and misogyny that have made rap a favorite target of the right wing. (Come to think of it, perhaps each of these realms will be chagrined to be likened to the other.) But as soon as you dig beneath the surface, the similarities between talk radio and gangsta rap are nothing short of uncanny. And these similarities are revealing, too. But before we get to the revelations, let’s examine the kinship. For great careers in both businesses you’ll need: EGO Extolling your greatness is nearly as crucial to rap as it is to talk radio. One consistent theme of Jay-Z’s lyrics is the genius of Jay-Z’s lyrics. He claims a charisma that is almost mystical and skills on the mic that make him the “Mike Jordan of recording,” “the Bruce Wayne of the game,” a “god.” Rush Limbaugh peppers his show with self-adulating incantations that would seem right at home on a Snoop Dogg track, calling himself “Chief Waga-Waga El Rushbo of the El Conservo Tribe,” “doctor of democracy,” and “a weapon of mass instruction.” Both he and Jay-Z have referred to themselves as “a living legend.” HATERS You’re nobody in hip-hop until you claim to have hordes of detractors. The paradox, of course, is that the artists who regularly denounce their haters have a huge and adoring audience. How does Lil Wayne complain in song about the legions who seek his ruin even as he dominates the charts? Ask Michael Savage, who is forever describing himself as an underdog, marginalized by the media — on the more than 300 stations that carry his show. FEUDS 50 Cent vs. Ja Rule. Lil’ Kim vs. Foxy Brown. Jay-Z vs. Nas. Every couple of years, one rapper will pick a fight with another and battle it out with the winner typically determined by sales. This will sound familiar to anyone who has followed, say, Bill O’Reilly’s broadsides at Mr. Limbaugh (“Walk away from these right-wing liars!” Mr. O’Reilly said of an unnamed rival, described as someone who smokes a cigar and owns a private jet) or Mark Levin’s attack on Mr. O’Reilly. (“He has a fledgling radio show, that has no ratings,” Mr. Levin said in 2008, “and he’ll be off radio soon because he’s a failure.” Levin’s predication came true in January of this year.) Liberal ranters can partake, too, as MSNBC host and fulminator par excellence Keith Olbermann has proven with his long running O’Reilly spat. VERBAL SKILLS Without them, you can’t rap and you’ll never make it as a talk radio opinion-machine. Free-style rap requires precisely the facility with words that it takes to free-associate for two or three hours a day. Forget, for a moment, what the Fox TV and radio gabber Glenn Beck is saying and marvel for a moment at how long he can say it — and how sharp and funny he can be. In a recent and genuinely hilarious bit, he lampooned the sleepiness of NPR talk shows by affecting a plummy British accent and repeatedly urging a caller — a member of his coterie in actual fact — to “please use your indoor voice,” though the caller was talking at a perfectly reasonable volume. Mr. Savage’s riffs are a quirky, zig-zagging flow of ideas that at their best are a kind of talk show scat, jumping from a mini-lecture about the Khmer Rouge, to a rave about barbecue chicken, to a warning that he feels a bit manic, which means he’ll be depressed for tomorrow’s show. If Mr. Limbaugh is conservative talk radio’s answer to Jay-Z, Mr. Savage is its Eminem — a man whose own neuroses are one of his favorite topics. Even beyond simple matters of style, rap and conservative talk radio share some DNA. Once you subtract gangsta rap’s enthusiasm for lawlessness — a major subtraction, to be sure — rap is among the most conservative genres of pop music. It exalts capitalism and entrepreneurship with a brio that is typically considered Republican. (Admiring references to Bill Gates are common in hip-hop.) Rappers tend to be fans of the Second Amendment, though they rarely frame their affection for guns in constitutional terms. And rap has an opinion about human nature that is deeply conservative — namely, that criminals cannot be reformed. The difference is that gangsta rappers often identify themselves as the criminals, and are proud of their unreformability. Finally, rappers and conservative talkers both speak for a demographic that believes its interests and problems have been slighted and both offer stories that have allegedly been ignored. Obviously, there are limits to all these parallels, but there is one more worth noting: rap has inspired its share of fear and now, liberals and moderates are asking the same question about conservative talk radio that conservatives have long asked about rap: How dangerous is it? There’s a curious role reversal here, with fans of Mr. Limbaugh, et al., now under the very suspicion that had long been cast on fans of gangsta rap. The suspicion boils down to another question: Can people listen to highly provocative words (and in rap’s case, irresistible beats) and still be civil? This seemed like a good question to pose to a man uniquely situated to opine about the shaded part of the Venn diagram of rap and conservative talk radio. I’m talking about DJ Clayvis, né Clay Clark, an Oklahoma-based, right-leaning talk show host and rapper. He has written anti-Obama raps, including “Audacity of Nope” and, though he believes his favorite talkers are sincere conservatives, he has long understood that his two different callings have a lot in common. “The differences between Ludacris and Rush Limbaugh are not that great,” he said. “Both have a huge egos, both bring a lot of bravado, both are sort of playing characters when they perform. And at the end of the day, they’re both entertainers.” Copyright 2009 The New York Times Company |

||||